The Breakthrough Prize Foundation, an organization created by investor Yuri Milner, has announced that it will commit $100 million over the next ten years to a new, large-scale SETIinitiative.

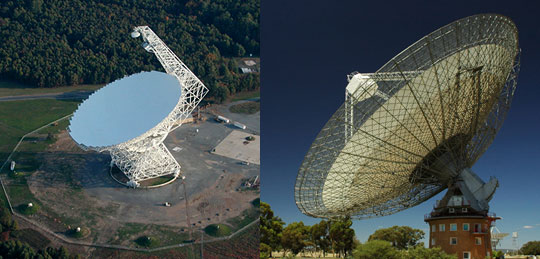

left – Greenbank observatory, West Virginia. right – Parkes observatory, Australia

left – Greenbank observatory, West Virginia. right – Parkes observatory, Australia

The intention is to use existing radio telescopes in West Virginia (the 100 meter Green Bank Telescope) and Australia (the 64 meter Parkes Telescope) to examine up to one million star systems for radio signals that would betray the presence of intelligence. The funding will allow the development of new receiving technologies that can speed up the search for radio broadcasts.

Beyond the nearby stellar targets, the project will also examine a large number of galaxies, as very advanced societies might be wielding high-powered signaling devices able to bridge intergalactic distances.

In addition to these radio SETI efforts, the Breakthrough Prize Foundation will underwrite an augmented search for laser flashes from the cosmos using a telescope at the Lick Observatory, in California. A further aspect of the initiative is to study the desirability and possible content of deliberate transmissions to nearby star systems, so-called active SETI.

Today’s announcement from the Breakthrough Prize Foundation is terrific news for all involved in SETI research. Private philanthropy plays an essential role in these efforts, and Yuri Milner’s contribution will fund SETI research on many fronts. The funding announced today does not go to the SETI Institute, but we are working with the Breakthrough Prize Foundation on other projects. The SETI Institute congratulates our colleagues and looks forward to joining them as additional Breakthrough Prize Foundation projects are rolled out. As ever, SETI Institute welcomes donations from all supporters of our work.

image credit: breackthroughinitiatives.org

image credit: breackthroughinitiatives.org

The following commentary was published on July 20 in various media venues, and describes the societal motivation for SETI searches. It was signed by SETI Institute scientists Seth Shostak, Jill Tarter, and Emeritus Board Chairman, Frank Drake.

Who are we?

A mature civilization, like a mature individual, must ask itself this question. Is humanity defined by its divisions, its problems, its passing needs and trends? Or do we have a shared face, turned outward to the Universe?

In 1990, Voyager 1 swiveled its camera and captured the ‘Pale Blue Dot’ – an image of Earth from six billion kilometers away. It was a mirror held up to our planet – home of water, life, and minds. A reminder that we share something precious and rare.

But how rare, exactly? The only life? The only minds?

For the last half-century, small groups of scientists have listened valiantly for signs of life in the vast silence. But for government, academia, and industry, cosmic questions are astronomically far down the list of priorities. And that lengthens the odds of finding answers. It is hard enough to comb the Universe from the edge of the Milky Way; harder still from the edge of the public consciousness.

Yet millions are inspired by these ideas, whether they meet them in science or science fiction. Because the biggest questions of our existence are at stake. Are we the Universe’s only child – our thoughts its only thoughts? Or do we have cosmic siblings – an interstellar family of intelligence? As Arthur C. Clarke said, “In either case the idea is quite staggering.”

That means the search for life is the ultimate ‘win-win’ endeavor. All we have to do is take part.

Today we have search tools far surpassing those of previous generations. Telescopes can pick out planets across thousands of light years. The magic of Moore’s law lets our computers sift data orders of magnitude faster than older mainframes – and ever quicker each year.

These tools are now reaping a harvest of discoveries. In the last few years, astronomers and the Kepler Mission have discovered thousands of planets beyond our solar system. It now appears that most stars host a planetary system. Many of them have a planet similar in size to our own, basking in the ‘habitable zone’ where the temperature permits liquid water. There are likely billions of earth-like worlds in our galaxy alone. And with instruments now or soon available, we have a chance of finding out if any of these planets are true Pale Blue Dots – home to water, life, even minds.

There has never been a better moment for a large-scale international effort to find life in the Universe. As a civilization, we owe it to ourselves to commit time, resources, and passion to this quest.

But as well as a call to action, this is a call to thought. When we find the nearest exo-Earth, should we send a probe? Do we try to make contact with advanced civilizations? Who decides? Individuals, institutions, corporations, or states? Or can we as species – as a planet – think together?

Three years ago, Voyager 1 broke the sun’s embrace and entered interstellar space. The 20th century will be remembered for our travels within the solar system. With cooperation and commitment, the present century will be the time when we graduate to the galactic scale, seek other forms of life, and so know more deeply who we are.